Yesterday, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change published their Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5’C

As policy makers and news editors across the world digested the implications of the findings and the stark warning that doing nothing is not an option if we want our children and grandchildren to live in a world with coral reefs and sea ice, at GFG Towers this got us wondering how we could do our bit (apart from cutting back on the Kobe beef suppers and trips to the corner shop in the Bentley).

And we thought perhaps exploring the impact that our western choices of funeral styles and goods have on the environment might be a good start.

Here are some facts.

In 2017, 607,037 people died in the United Kingdom and of these, 467,748 were cremated.

This represents 77.05% of all deaths (in comparison with 1960, when 204,019 people or just 34% of all those who died were cremated)*

*Figures obtained from the Cremation Society of Great Britain Pharos International UK Cremation Statistics issue.

Now for the more intricate bit. The effect of the funeral choices for these 607,037 people on our environment.

This is surprisingly hard to find accurate, up to date and unbiased information about. There are lots of quoted figures for the environmental impact of different choices, but it’s extraordinarily hard to substantiate any of them. It also makes sense to try and find out where the figures originally came from, and consequently, who paid for the research. There are very vested interests in this area.

All this following-of-links is time consuming and frustrating, so we’ve just cited the sources of the information below. And we gave up trying to establish the carbon cost of funerals, it would just be guesswork on minimal accurate information, and a variable way of measuring. But suffice it to say that there is a cost. A significant one. Funerals require a lot of energy to create the way we currently do them. And the need to dispose of our dead isn’t something that is going to go away.

Currently, more than three quarters of people who die in the UK are cremated. So we’ve focused on this.

Cremation – or the incineration of the bodies of those who have died (although incineration is frowned on as a term by the sector, it has ugly historical / industrial connotations) – is clearly not a good thing for the environment.

We’ll try to explain why, but a warning – it quickly gets complicated and the sentences get longer and longer.

The average weight of a middle aged British adult is 70kg for a woman, 83.6kg for a man. Source: ONS

The average weight of the cremated remains handed back to a family after the cremation has taken place is roughly 3.5% of the weight of the person who died. Source: Cremation Institute

Approximately 60% of the human body weight is water – Source: US Geological Survey’s Water Science School

So, by our amateur calculations, after allowing for the percentages of weight of water content and the ‘cremains’ returned following cremation, there’s a conservative third of a person – or around 20kg – that has disappeared in the combustion process.

Is that right? If so, even allowing for the fancy filtration equipment capturing the nastier elements en route, that’s a whole lot of potential emissions going through the flues and up the crematorium chimney stack. Per person. Multiplied by 467,748 in 2017.

DEFRA offered some Statutory Guidance for Crematoria in 2012 – below is an extract from those guidelines, listing some of the potential pollutants from the cremation process and the techniques to control them:

Techniques to control emissions from contained sources

Particulate matter(PM)

Particulate matter in unabated cremators is controlled by good combustion and by gas flows that do not carry particles out of the cremator. Mercury abatement further lessens emissions of particulate matter.

Hydrogen chloride

Hydrogen chloride mostly arises from the salt content of bodies. Chlorine should be avoided by careful control of coffin materials, contents, shrouds, clothing and items other than the body itself. Condensation is prevented by dilution and preheating stacks. Mercury abatement further lessens emissions of hydrogen chloride.

Mercury

Mercury is highly volatile and therefore almost exclusively passes into the flue-gas stream. Mercury is only partially removed with particulate matter. The rest remains in the flue gases as volatile compounds. Where activated carbon is used as part of the abatement technique, operators should be aware of potential health and safety risks arising from spontaneous combustion.

Volatile organic compounds

Volatile organic compounds are controlled by good combustion.

Dioxins

Good combustion and low particulate matter emissions minimise the emission of PCDD/F (polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins and polychlorinated dibenzofurans often referred to as ‘dioxins and furans‟or even just „dioxins‟). Mercury abatement further lessens emissions of dioxins.

Nitrogen oxides

Nitrogen oxides arising from coffins might be lessened by switching from coffins made using board made from wood and nitrogen-containing resins. However plain wood is considered too expensive to be required as Best Available Technique (BAT). Cardboard caskets also contain nitrogen in the wet strength additives. Nitrogen is always present in the body. Thermal NOx is minimal due to the secondary chamber temperature and because combustion is staged over primary and secondary chambers.

Carbon monoxide

Carbon monoxide is a pollutant but is also the prime indicator of incomplete combustion that would emit un-burnt hydrocarbons, PAH and PCDD/F, which are much more difficult to monitor. Abatement of carbon monoxide is not BAT but good combustion minimises emissions.

Carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide emissions are minimised by cremator design and operation. Simple recording of gas consumption and conversion into CO2 equivalent emissions enables monitoring of emissions. Although not BAT, gas meters allow measurement of gas consumption, and comparison with other sites, including the potential for cost savings. Advances in combustion control, allied with short period carbon monoxide monitoring to monitor good combustion, may allow significant reduction in carbon dioxide emissions for next generation cremator designs.

Hmm. Not quite sure what that all means. But it’s good to know that emissions are being monitored.

Let’s just pick up the mercury point. According to this 2015 Reuters article, the average cremation releases 2 – 4 grams of mercury.

Now, here in the UK, DEFRA got involved back in 2005, and in conjunction with the Implementation of OSPAR Recommendation 2003/4 on Controlling the Dispersal of Mercury from Crematoria Second Overview assessment, required 50% of all cremations at existing crematoria to be subject to mercury abatement by the end of December 2012, with all new crematoria being required to fit mercury abatement. See here.

Because of the difficulties installing abatement equipment in some crematoria, or problems funding the costs involved, an ingenious burden sharing scheme was introduced by the sector, enabling crematoria that installed mercury abatement equipment to derive income by trading 50% of the cremations they undertake. This meant that other crematoria (those without the abatement equipment) could pay for these ‘tradable mercury abated cremations’ in order to become compliant.

This system continues, and despite the UK being a contracting party to the OSPAR Hazardous Substances Strategy that requires 100% mercury abatement by 2020, we haven’t been able to find out with certainty that further progress is being made to reach this target. In the meantime, the level of 50% of cremations having their mercury abated is, apparently, satisfactory.

According to the 2016 Implementation of OSPAR Recommendation 2003/4 on Controlling the Dispersal of Mercury from Crematoria Second Overview assessment the UK states that ‘The data received from Local Authorities recorded in 2013 for England and Wales showed there were more than 330,000 cremations with around 75% of those recorded abated.’

If we apply that same figure to last year’s cremation numbers, and if we use the figure cited by the UK in their response to OSPAR of 0.9g mercury emitted per person cremated without mercury abatement technology (and that’s a very conservative figure – remember that Reuter’s article suggesting the average cremation releases between 2 and 4g of mercury?) then 25% of the 467,748 cremations in the UK in 2017 would have generated at least 105 kilograms of mercury into the atmosphere, drifting towards the North East Atlantic to embark on the process of bioaccumulation into our food chain.

The US Environmental Protection Agency recommends a maximum daily consumption of a daily intake of 0.1 micrograms per kilogram of body weight, or, in other words, for an average adult, 8 micrograms per day.

(If you’re not keeping up at the back, that 105 kg of mercury created by last year’s cremations in the UK = 105,000,000,000 micrograms. Or, if you prefer, a hundred and five thousand million micrograms)

NB according to the same aforementioned Reuters article, some 200,000 babies are born each year in the EU with mercury levels harmful to their development.

We’ll just leave that point there.

We’ve got a bit sidetracked by the numbers and the intricacies of potential cremation emissions (whether financially offset or not) so apologies for that.

And we haven’t even touched on the cost of the energy involved in firing up and running all the cremators in the UK’s crematoria, let alone the environmental costs involved in the manufacture of all that cremation equipment or the buildings it is housed in. (There are over 290 crematoria in the UK, with more going through the planning process as we write, and pretty much all of them will have several cremators in use.)

We also haven’t got around to the impact of all those nice varnishes, plastics and adhesives being burned throughout the country every day, nor the energy involved in manufacturing and delivering all those coffins. Or all the floral tributes. Remember, there were 467,748 cremations in 2017. That’s a lot of coffin sprays.

Back in 2010, the Burial and Cremation Information Trust created a comprehensive Carbon Questionnaire for crematoria – a document which clearly took a huge amount of time and input to put together.

Unfortunately, we’re not sure which, if any, crematoria have taken the time to complete it. We’ve looked, but we couldn’t find any publications from crematoria citing their work to reduce their environmental impact. There certainly doesn’t appear to be anything in the public domain indicating that there has been an industry wide initiative to establish a base line of the environmental impact that cremating our dead is having.This, we think, is a real shame. We would like to know this.

Anyway, back to the broader subject of environmental decision making when it comes to funerals.

It’s apparent that cremation isn’t ticking many environmental or sustainable boxes. Or any, actually. But unfortunately, choosing a traditional burial also comes with an environmental price tag if you want a traditional burial in a double or triple depth grave and a memorial made from imported stone.

No, if you’re really concerned about the environment, and you want your funeral to have as little detrimental impact on our planet as possible, choosing a natural burial in a site local to you that is well managed according to ecological principles is the only option.

There are hundreds of natural burial sites around the UK – see here for a map, or visit the Natural Death Centre for a list of members of the Association of Natural Burial Grounds.

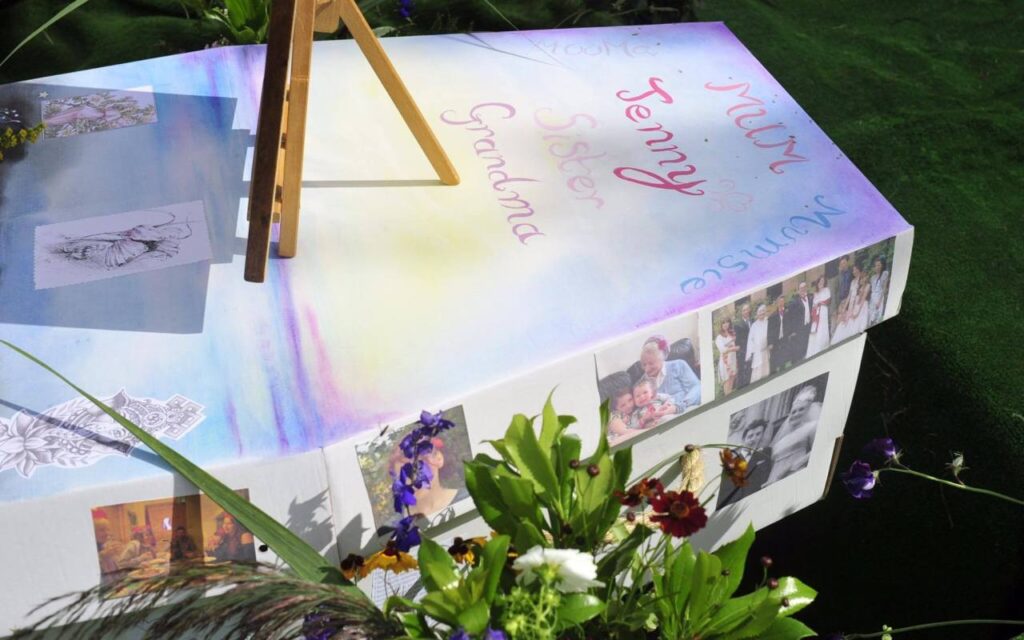

A natural burial comprises of burial in a shallow grave, in a biodegradable coffin or shroud, and with no permanent memorial – see here.

And if you want to think about the bigger picture, below are the elements of any funeral where you can make a sustainable choice rather than one that comes at an environmental cost as well as a financial one:

Embalming.Not good for the environment. Even if eco-friendly embalming fluids are used, the process still requires flushing litres of blood into our sewage system. Good funeral directors can care for dead people without having them embalmed.

The type of coffin. Made from mahogany or other rainforest timber? Steel American casket? Not good for the environment. The typical MDF (chipboard) veneered standard mid-price coffin isn’t much better. Ask for coffins that are locally made, from FSC certified, sustainably sourced wood or willow, wicker or papier mache. Or choose a linen or woollen shroud.

Flowers. Plastic frames for letters spelling out words or names? Oasis? Imported flowers that have already travelled thousands of air miles? Not good for the environment. Pick flowers from your garden, or donate to a charity instead.

Travelling to the ceremony. Big gas guzzling hearse and following limousine? Lots of people travelling in cars from a distance? Not good for the environment. Ask for an eco-hearse and car share instead.

Choosing a memorial. That lovely granite tablet that looks so shiny? The pure white marble headstone? Not good for the environment.

The maintenance of the grounds. Manicured lawns, bedding plants and tidy rose gardens in crematoria grounds, intensively mown and weeded cemeteries – not good for the environment. Choose somewhere with conservation areas and a policy for encouraging biodiversity.

- The indomitable Ken West MBE published an article a while back entitled ‘How Green is My Funeral’ with a handy calculator of the environmental impact of the various choices involved. You have to turn your head 90’ to read it unless you print it out, but it’s well worth the effort.

And our friends at Leedam Natural Heritage have also produced a table showing the different options for consideration by the environmentally conscious when deciding on which type of funeral they want.

We’d love to know what you think about all this.

As the IPCC is urging us to pay attention to the environmental impact of all aspects of our lives, should we not also be considering the environmental impact of our deaths?